Baku, Azerbaijan

August 27, 2007

By Dan Murdoch

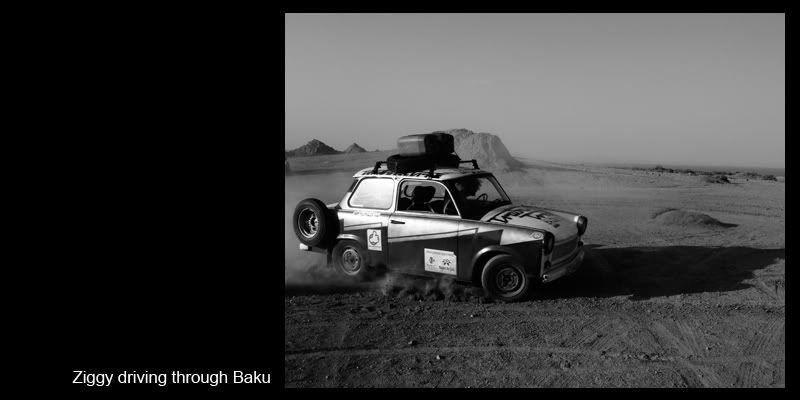

THE cop pointed his red flag at our car and blew his whistle hard.

I felt like I’d been pulled over while go-karting.

Our entire convoy had just followed J Love into a U-turn on the motorway, a manoeuvre that would be illegal in most civilised countries, and Azerbaijan was no exception.

Ziggy and Gunther the Merc had managed to get away, but I was left to face the music with the occupants of Fez.

My experiences in Azerbaijan over the preceding day and night had all been good. The people seemed friendly – one family had flagged us down on the motorway to insist we join them for dinner, and in the foreigner-friendly capital of Baku I expected the police to be reasonable.

The cop ambled over in his own time, and I took my sunnies off, grabbed my identification and left the car to meet him with my best silly but harmless foreigner smile.

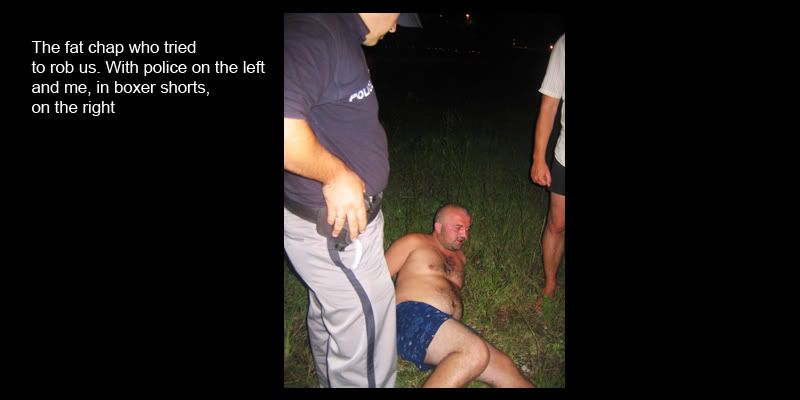

“Salam” I offered my hand, which he took firmly. The bones in my knuckle have yet to heal from our incident with the thief and I winced as the pain shot through my palm.

“a’lekum a Salam.”

He seemed affable enough, but spoke no English, and I used my handful of Russian words to explain what we were doing.

He let me know there was a problem and led me back to his car where he sat me down in its relative privacy. He took my details and made a great show of writing out a ticket.

The BMW felt shiny and new and smelt of leather – it was strange being in a proper car after so long in Trabants.

The cop sucked the air in through his front teeth, making a gurgling sound. He seemed to be weighing me up.

He flipped over the ticket and wrote on the back:

$150.

Three cars, fifty dollars each, he communicated through the universal language of hand.

I pulled a face which I hoped conveyed confidence in my position but respect for his, and shook my head.

“Nyet dollar. Nyet.”

There was a silence at this impasse. He looked more disappointed than angry.

“Ya rabotayu journalista v’London”

I work as a journalist in London, I told him as casually as I could, hoping the latent threat would come across without sounding challenging.

“Journalista?” he raised his voice, then tried to work out my age from my passport.

“24,” I tried to help him, raising my fingers.

Again using sign language, he asked whether I was married or had children, and was surprised when I said no. Then he asked if Zsofi, who had been in Dante with me, was my girlfriend. I said no and he made a crude gesture to ask if I was sleeping with her.

I laughed in a ladish way and said no but he nudged me and winked all the same, apparently adamant that two people could not share a car without fornicating.

He looked down at the back of the ticket where $150 was neatly written.

“Ya rabotayu journalista v’London,” I repeated, pulling my press card out of my wallet and handing it to him. He grunted, and shouted out of the car window to a colleague who had a few more stars on his shoulder.

He showed him the card and they exchanged words.

$50 was written on the back of my ticket.

I found it ridiculous that he was writing the amount he wanted as a bribe on the back of the official ticket and, to hide any compliance on my part, scrawled $10 in my notebook.

He seemed to give up.

“Ok, Daniel.” He waved me away and I left the car.

Dan 1, Cops 0.

“Baku is oil. That’s why everyone’s here,” the man shouted into my ear, spraying the side of my face with spittle. He was northern and drunk, but it was late and I was in an Irish bar – what could I expect. The only locals in Finnegan’s Irish Pub in Baku were hired hands – barmen, doormen and whores.

A live band was playing and an Azeri was singing Dancing in the Moonlight, but he clearly couldn’t speak English because evabadey waz danswing in the moonliy.

The Trabbi girls didn’t seem to care, frolicking and having drinks bought for them.

“It’s boom town. The oil’s bubbling out of the ground. Everyone wants a bit. It’s the English that have got it though.”

I wiped my cheek. There are a lot of ex-pats in Baku, enough to warrant two English language newspapers, and British Gas has a large interest in the city.

Oil platforms hover just off the coastline and stretch out into the Caspian Sea. Pipelines crisscross the surrounding countryside.

People have been going to Baku for oil for their lamps for thousands of years. Marco Polo said there were different coloured oils in different areas, blue, red, green and yellow, with yellow being the most popular. The world’s first offshore well was drilled here in the mid 19th Century.

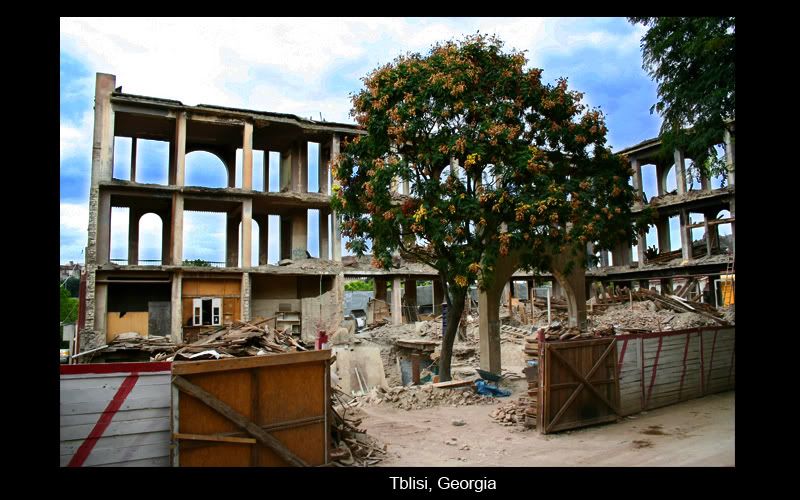

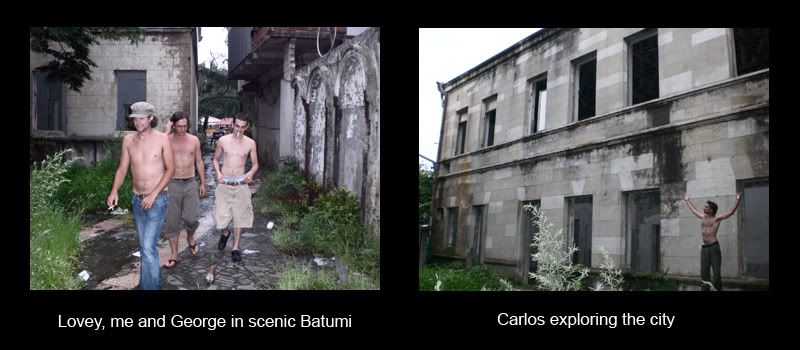

The city is a strange mix of neo-classical, neo-neo-classical, and dilapidated. But you can tell the money’s here –construction is everywhere, McDonalds is everywhere.

The following day I was sitting on a step in the shade of a Birch tree, reading and waiting for Brady and Zsofi to finish in a shop. I heard shouting and looked up to see a cop demanding I move. I stood up, put my bag back on my shoulder and moved to the side of the road. There’ll be no sitting on the street in Azerbaijan.

Dan 1, Cops 1.

The departing cop was pulled over by a well-dressed local at the restaurant I had been sitting near. They argued, the cop left, then the man called me over:

“You can sit there,” he said, then gestured at the policeman: “He doesn’t know the rules.”

I sat down and the cop glared at me as he shuffled off.

Dan 2, Cops 1.

The man was dressed in a well-fitted suit, with gold cufflinks and an expensive watch, and dining with men of similar attire.

“Why did he move me?”

“He thinks it is still Soviet times. Beggars used to sit on the ground,” he shrugged, “but it’s ok.”

I looked a little like a beggar. Dirty, stained shorts, rolled up over my knees, sweaty, creased shirt and long, unkempt hair that had taken the shape of a thatched roof.

“Are you a tourist?”

I explained my mission.

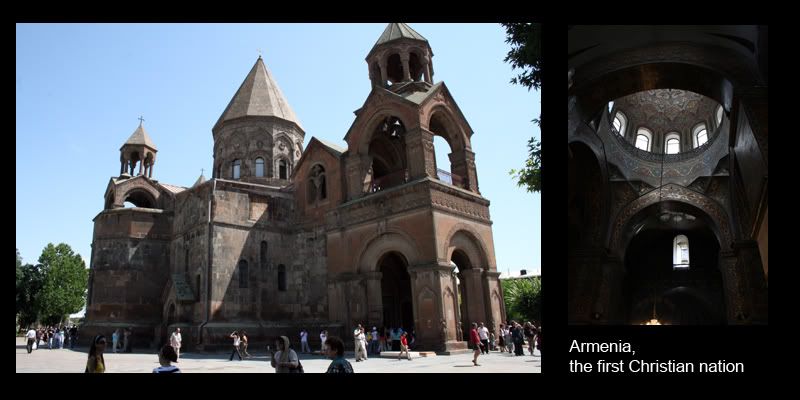

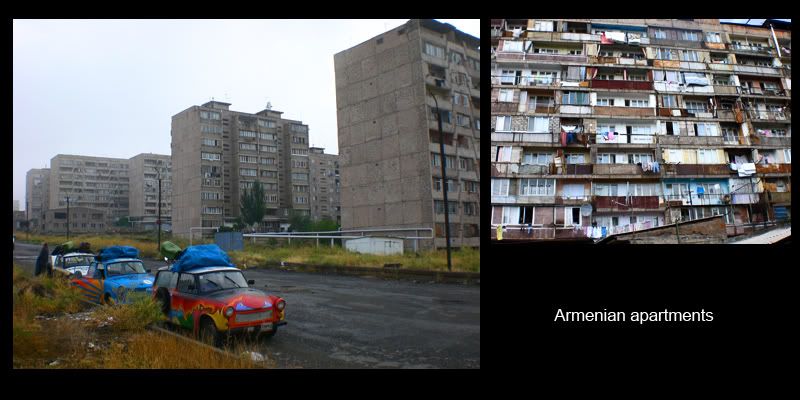

“What was Armenia like?”

“They told me all Azerbaijanis were evil,” I told him in a horribly miscalculated comedy gambit that only served to get his back up.

The two countries are at war.

“We are all Caucasian, we are the same people.”

And he returned to his business.

Baku is hung with pictures of the country’s former president Haydur Aliyev, and its new one, his son Ishmail.

Despite Azerbaijan being a ‘democracy’, arrangements were hastily arranged for a hereditary transfer of power when Aliyev Snr became ill a few years ago. He son was quickly promoted to prime minister and thrust into the public eye.

When old Aliyev popped off, the power of his political and electoral machine was handed to his son, who waltzed into the hot seat at the subsequent presidential election.

Images of the two of them are everywhere: paintings in shops and homes, billboards along the roads, signs in police stations, shrines by the road. Another personality cult.

But stability in oil rich Baku is vital to the west, and world leaders are happy to overlook the Aliyev’s abuses of power to ensure their fuel supply remains uninterrupted. As long as Baku is needed for the world’s oil then the world has an interest in Baku’s stability. And the Aliyev’s are good trading partners.

We visited the ‘mud volcanoes’, where liquid mud bubbles and belches from the peaks of hills. The fractured landscape looked like the moon, the mud had been erupting for thousands of years, forming a dry, cracked landscape of mud-flows and shapes.

Later I went out to the cars and found a gaggle of cops looking over them. I took one off them, Captain Sayeed, up to our host’s apartment for a chat.

Later I went out to the cars and found a gaggle of cops looking over them. I took one off them, Captain Sayeed, up to our host’s apartment for a chat.“That’s the nicest cop I’ve ever met,” our host said, “Six years ago they were like beggars – they went round asking for money. That was the system, even with the big guys. Now they make the salary higher so they don’t have so many problems.”

But they still ask for money.

“If you make a little mistake then yes, they make you pay. But before, whether you made a mistake or not, they would ask for money. Everyone pays, I pay, my father pays.

“People do not know any better – this is how it has been for years. People don’t know how much a speeding ticket should cost, so they pay whatever they are told.”

“There is corruption on every level,” an Azeri friend later told me, “example, the government says in the budget that it is spending so much on repainting buildings, but this does not cost as much as they say. So where does the excess go? In their pockets.

“We have so much oil, we could be such a rich nation, but look at the statistics, a teacher earns $100 a month.”

In order to avoid Iran, we needed to get a ferry from Baku, across the Caspian, to the Turkmen port of Turkmenbashi.

There were no fixed prices on display at the port and we were resigned to entering into negotiations.

Four cars and nine people. How much to Baku?

The price started at an extortionate $1,350 but OJ and I negotiated it down to $1,100 over two sweaty hours.

It felt infuriatingly expensive so we took a break to talk about it, and phone the British Embassy for advice.

I got through to Sayeda Zayeva. She agreed that the fee seemed expensive: “But this is private matter, we cannot get involved.”

“Do you think I'm being bribed?”

She laughed, “Of course. This is Azerbaijan. This is how it works.”

“Well, is there anyone I can complain to?”

Another giggle, “No, this is Azerbaijan.”

“So what should I do?”

“Do you have any other way of getting to Turkmenistan? Do you have any other choice?”

“No.”

“Then you pay. This is Azerbaijan, this is how things work.”

We grudgingly paid up, but on our way from the ticket office we got hit for a random $30 ‘road tax fee’, presumably for using the strip of tarmac between the port gates and ferry, a $44 bridge fee for a goon to open a gate onto the ferry, a $10 per car loading fee, and $10 per person to be shown to our cabins (which we refused to pay).

They told us the boat would take 12 hours.

It took three days.

Ends

mrdanmurdoch@gmail.com