Putin: spies, murders, poisons and hacks.

RussiaNovember

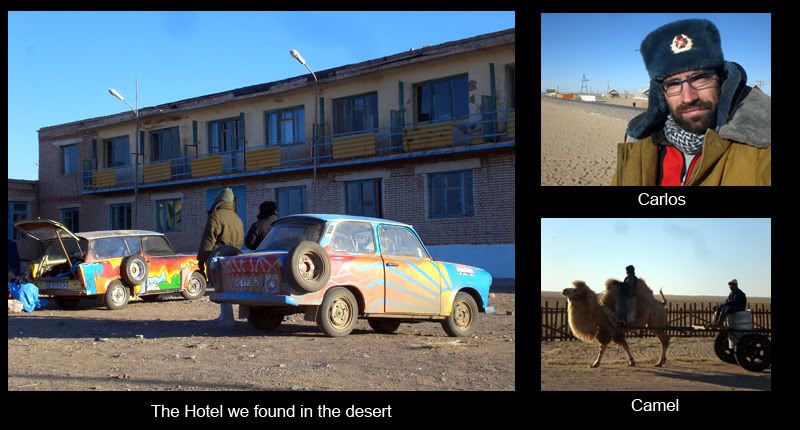

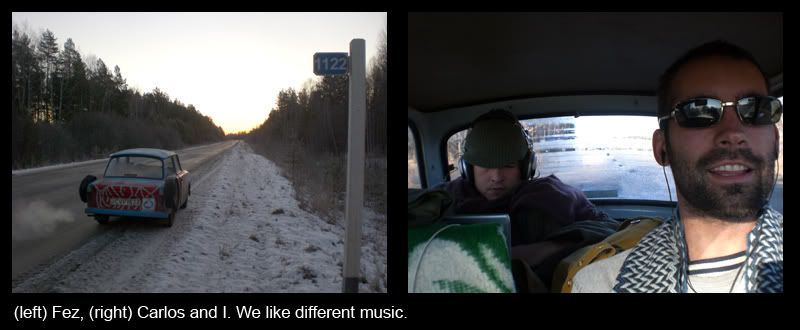

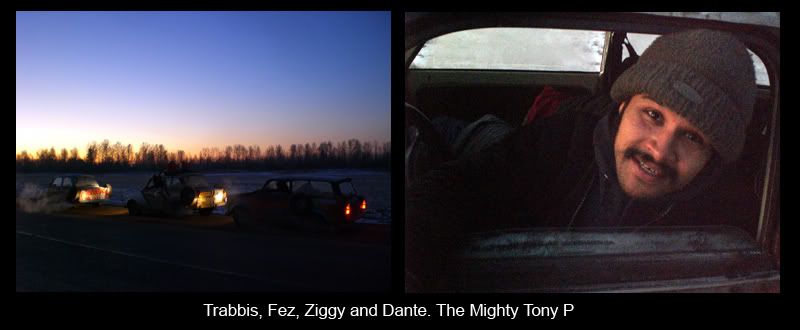

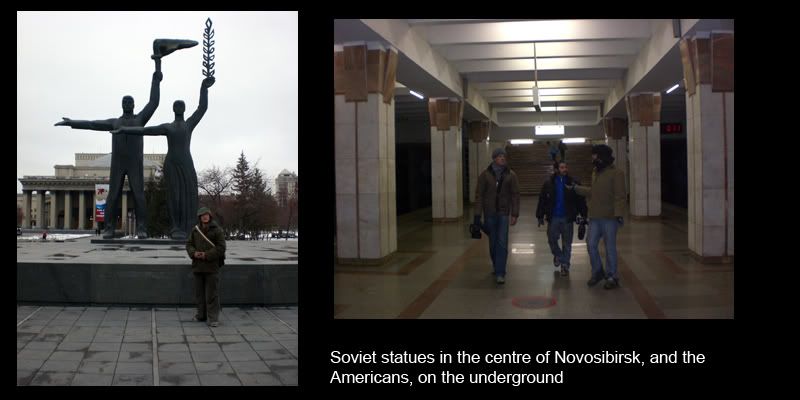

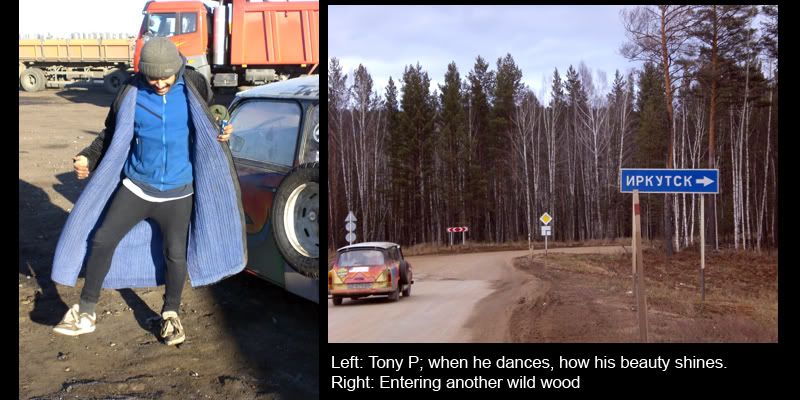

By Dan MurdochPHOTOBUCKET DOWN SO SORRY, NO PHOTOS

"Society has shown limitless apathy... As the Chekists have become entrenched in power, we have let them see our fear, and thereby have only intensified their urge to treat us like cattle. The KGB respects only the strong. The weak it devours. We of all people ought to know that." Anna Politkovskaya, Putin's Russia: Life in a Failing Democracy.

PUTIN.

The balding Russian president isn’t too popular in the Righteous West right now, and I was keen to see how the former KGB spymaster was perceived on his home turf.

Back home the press echo our leaders concerns over the moves of old Vlad with phrases like ‘limiting democracy’, ‘restricting political opposition’, ‘concentrating power’, ‘returning to a Soviet dictatorship’, and that terrible sin of ‘curtailing press freedom’ (Patriot Act anyone?: http://www.bordc.org/threats/speech.php).

According to Vsevolod Bogdanov, the chairman of the Russian Union of Journalists, 261 Russian journalists have been killed since the fall of the Soviet Union, and only 21 cases have been solved.

The most high profile example occurred in October last year, when Russian journalist Anna Politkovskaya, a vocal critic of Putin’s administration, was gunned down in her apartment building.

The 48-year-old had accused Putin of ‘state sponsored terrorism’, and revealed a host of atrocities and rampant corruption in Chechnya, where Putin launched a grim war against insurgents.

Working in a country few journalists dare to cover, Politkovskaya reported on the Russian-backed military engaging in torture, abduction and murder, and claimed huge sums of war cash were being embezzled.

She made plenty of enemies in Chechnya, including the Chechen Prime Minister, who she called a ‘coward armed to the teeth’.

"We are hurtling back into a Soviet abyss, into an information vacuum that spells death from our own ignorance. All we have left is the internet, where information is still freely available. For the rest, if you want to go on working as a journalist, it's total servility to Putin. Otherwise, it can be death, the bullet, poison, or trial - whatever our special services, Putin's guard dogs, see fit."Anna Politkovskaya, Poisoned by Putin, Guardian Unlimited, September 9, 2004

In 2001 she was detained by the military in Chechnya and subjected to a mock execution. In 2004, on a flight to the Beslan school siege, where she was to help with the hostage negotiations, she became violently sick and lost consciousness after drinking a cup off tea. She claimed to have been poisoned. Yet she kept working. She received death threats as a matter of routine, but continued with a determination bordering on fanaticism. Probably a feisty sort.

She won a plethora of international awards, but her influence as a journalist was limited. She was banished from state-controlled public television and wrote for the small Novaya Gazeta, a bi-weekly with a readership of 100,000 people.

I think it would be fair to say that, sadly, her death had a greater impact on the world than her life.

The murderer has not been found.

"We'll follow terrorists everywhere. We will corner the bandits in the toilet and beat the hell out of them." Putin on Chechen extremists.

A few days after the murder Putin was in Dresden for the annual Russsian-German meeting known as the Petersburg Dialogue. Around ten thousand protestors gathered to call Putin a murderer, and I find his response quite revealing. He told reporters: "This journalist was indeed a fierce critic of the current authorities in Russia and Chechnya.... (but) her impact on Russian political life was only very slight. She was well known in the media community, in human rights circles and in the West, but her influence on political life within Russia was very minimal.”

Later he added: "In my opinion murdering such a person certainly does much greater damage from the authorities’ point of view, authorities that she strongly criticized, than her publications ever did. Moreover, we have reliable, consistent information that many people who are hiding from Russian justice have been harbouring the idea that they will use somebody as a victim to create a wave of anti-Russian sentiment in the world."

So what did he have to gain from her murder? He has a point.

The person ‘hiding from Russian justice’ was widely interpreted in the Russian media to be Boris Berezovsky, a man who had met Politkovskaya more than once. The billionaire, who once held the high government post of Secretary of the Security Council, now lives in London, from where he has announced he is campaigning to overthrow the Russian government. Is this a man ruthless enough to murder his allies to spite his enemies?

I saw him on Question Time once. He shouted and waved his arms around a lot in the Russian style.

Putin’s point could also be raised when considering 2006’s ridiculously Bond-esque Alexander Litvinenko poisoning- a story you really couldn’t make up. Who poisons someone in this day and age? And what fool would use a substance almost only employed by the KGB, that’s so radioactive it left a trace across London, and takes a few weeks to do away with its victim, allowing him to scream giddy accusations till he snuffs it.

Very dodgy.

In the 90s Litvinenko worked as a bodyguard for Berezovsky, but then flipped out and openly accused his FSB (the new name for the KGB) bosses of ordering the oligarchs execution. He was arrested, then released and fled to London where he was granted asylum and again got chatting with his old friend Berezovsky.

While in London he wrote a book claiming that the FSB organised the 1999 Moscow apartment bombings, which killed 300, and helped organise the 2002 Moscow theatre siege. Both events helped Putin gain greater support and funding for his war in Chechnya. He also accused them of murdering Politkovskaya, who he knew, and said Putin had been involved in organised crime.

When the book was published, Russian authorities confiscated 4,000 copies on route to Moscow.

So far so feasible, but he also went on record claiming Putin was a paedophile, and that Italian PM Romano Prodi was a KGB agent.

Sounding a little more like a cranky conspiracy theorist now Alex.

The simple conclusion to the Litvinenko case is that the FSB did it (see picture of FSB agents using his photo for target practise). But in my mind his death lends more credence to Putin’s suggestion that his enemies are trying to ruin Russia’s reputation. What did Vlad have to gain from the murder of one slightly bonkers dissident.

Though Vlad didn’t help himself by refusing to let British police interview their prime suspect, the former-FSB agent Andrei Lugovoi.

While working on the cars one night I raised this with an off-duty policeman: “So Andrei Lugovoi can fly to London, leave a trace of Polonium 210 across the capital, meet Litvinenko in the restaurant where he was poisoned, then fly back to Russia, and British investigators aren’t allowed to interview him. Is that fair?”

“Hahaaaa,” he slapped me on the back, “this is Russia, whatever Putin says is fair.”

“Do people think it was Lugovoi?”

“No people don’t care, Litvinenko was crazy, he had many enemies. The Kremlin says Berezovsky did it. And why not? This way he harms Russia yes?”

If you think about who benefited from both the Litvinenko and the Politkovskaya murders, it wasn’t Putin. In fact both damaged Russia in the eyes of the West- had you heard of either before their deaths?

And if his enemies are willing to murder their own champions in order to get at Putin, he has every right to be a touch paranoid.

In 2004 there was another poisoning, this time Viktor Yushchenko, the West-leaning Ukrainian opposition leader. He almost died after being struck down at the height of the county’s presidential election. He won the fight for his life, and then the election, but has been left horribly scarred.

In September this year Yushchenko told The Times newspaper that Russia had blocked investigations into the poisoning: “Three laboratories in the world were producing dioxin of this formula (the poison). It is very easy to determine the origin of the substance; there is nothing magical about it.

“Two laboratories provided samples but not the Russian side. This of course limits the possibilities of the investigation process.”

He added that Russia had refused to let Ukrainian prosecutors interview their three prime suspects.

(It should be noted that Yushchenko said this three years after the event, and just before the Ukrainian elections. Not that I'm suggesting that campaigning politicians make cynical attempts to win favour and slur their opponents.)

An Irkutsk taxi driver in his 50s: “Even if Putin is using his KGB ways, why should I care. Russia is getting strong again, the world will notice us. Who was this Politkovskaya? Wasn’t she the mad woman? People get shot in Russia, especially mad people who write mad things.”

Even if we discount the Litvinenko, Politkovskaya and Yushchenko affairs as conspiracy theories, there are plenty of other things Putin does to get up the West’s nose.

He supports Iran in its tug-of-war with the UN over the country’s nuclear ambitions, cemented by his recent trip to Tehran- the first visit to Iran by a Russian leader since WW2, and a deal to provide the country with enriched uranium for its civilian reactors.

He has stoked up the rhetoric against the US, accusing Bush of making the world a less safe place by throwing his weight around.

He, in my opinion completely fairly, opposes US plans to build a nuclear shield over the West by stationing interceptor missiles along the Russian border (this is a little inflammatory). The Yanks claim the shield is to protect them from North Korea and Iran. Putin cleverly suggested they use an old Soviet missile base in Azerbaijan, and others in Turkey and Iraq, much better placed to protect against Iran but in no way neutralising the Russian armoury.

Bush has yet to get back to him on that one.

“There are no such missiles – Iran does not have missiles with the range. The defence system would be] installed for the protection from something that does not exist. Is it not sort of funny? It would be funny if it were not so sad.

“We have brought all our heavy weapons beyond the Urals and reduced our military forces by 300,000. But what do we have in return? We see that Eastern Europe is being filled with new equipment, two positions in Bulgaria and Romania, as well as radar in the Czech Republic, and missile systems in Poland. What is happening? Unilateral disarmament of Russia is happening.” Putin.

Putin claims the US military actions and spending are forcing Russia into a new arms race, and just last month, on his annual, three-hour, live television phone-in, said that Russia would continue development of a new generation of nuclear weapons. He said Russia was upgrading its nuclear arsenal, including intercontinental ballistic missiles, nuclear submarines and strategic bombers. It was also developing "completely new strategic [nuclear] complexes”.

"Our plans are not simply considerable, but huge. At the same time they are absolutely realistic. I have no doubts we will accomplish them," he said.

A little disconcerting, but understandable if seen as a reaction to US military spending.

He has also made a recent grab for a large chunk of the resource rich Arctic by claiming it is actually a part of Russia’s continental shelf. That one will take a while to resolve.

Then there’s his pursuit of the oligarchs.

The oligarchs are the men who made billions when the Soviet Union broke up and state owned assets, particularly in the energy sector, were sold off at a fraction of their true worth. It turned middle managers like Chelsea-owner Roman Abramovich and Berezovsky into some of the richest men in the world. Many of these men then bought into the media to add political power to their financial clout.

But Putin has waged a war against them, many have faced charges of corruption forcing them to flee or been sent to prison. One example is Mikhail Khordorkovsky, the former president of Yukos Oil. He bought the company when it was privatised in the 90s for £55million. In 2004 it was worth £15billion.

Even with shrewd management that’s some growth, and there is little doubt the company was hugely undervalued when Khordorkovsky bought it.

A couple of years ago Khordorkovsky was jailed for corruption and fraud. Yukos has been forcibly taken back into state control. The liberal West saw it as a political move because Khordorkovsky was funding Putin’s opponents. But Putin claimed Khordorkovsky was involved in organised crime and corrupting Russia’s parliament, the Duma.

In the West this often appears to be a communist style campaign against the wealthy. But there is a stink about some of these oligarchs: Berezovsky is currently being investigated in Brazil for alleged money laundering involving football clubs. Khordorkovsky faced constant accusations of links to crime.

But because of the West’s mistrust of Putin’s motives, it is hard to separate the truth from the propaganda.

I asked George, a 22-year-old student from Novosibirsk, what he thought: “These men stole the wealth of Russia. The stole the natural resources from the people and made themselves very rich. Now it is right that we take this money back.”

What about Yukos?

“It is right that the people get the benefit of the country’s resources, not just a handful of men. Why should some people have billions of roubles from Russia’s oil and the rest of us have nothing?”

The clampdown on political opposition has become even more incendiary and blatant in the run up to next month’s presidential elections.

In May several opposition leaders, including western journalists and former world chess champion Gary Kasparov, were arrested and detained on their way to an EU-Russia summit. Kasparov was planning to lead a rally by Other Russia, a group opposing the Kremlin.

As he was being surrounded by police, Kasparov shouted at reporters: "It is an authoritarian regime. Putin is not a democrat. Europe's leaders need to address this issue. It is ridiculous when a Russian citizen with a good biography is not allowed to travel."

He added that Russia was obliged, under international law, to allow freedom of assembly. "We have no access to TV or parliament. The only way for the opposition to protest is through non-violent demonstration.”

Putin has now served two four-year terms as President, the maximum allowed, and according to the constitution, must stand down at the elections.

But there is nothing in the constitution banning him from becoming prime minister, and it seems that is his plan. He will ensure a weak president is elected, who relies on Putin’s power base and will probably be little more than a puppet. Then, at the next presidential elections in four years time, perhaps he will stand again?

This move would of course attract huge amounts of criticism from the West. But Russia is a fledgling democracy, absolute monarchy was only dropped in 1917, then followed 64-years of Soviet dictatorships. Democracy has only been around for 16 years: it needs time to settle. In the US women only got the vote in the 20s and blacks in the 60s, even now it can hardly be considered a perfect democracy (2000 elections?). In Britain we have a mostly hereditary second chamber, complimented by political appointments (cash for peerages?): not quite the rule of the people.

So although Western criticisms are justified, some sense of perspective is needed.

“Russia will not soon become, if it ever becomes, a second copy of the United States or England - where liberal value have deep historic roots.” Vlad Putin.

I asked people across Siberian Russia what they thought of their judo-throwing leader, and, pretty much universally they showed their support. Always I heard that he is ‘a strong leader’.

Asya, a 21-year-old student: “He is a good man, a very strong leader. We love him here because Russia needs a strong leader at the top. Not like Yeltsin. Yeltsin was weak. After that the whole country needed someone to take us forwards.”

Would you be happy for Putin to remain as president?

“Yes. Who else is there? The opposition are jokers. There is no one else as good as Putin so why not keep him?”

A sentiment I'm sure Vlad would love to hear.

Ends

mrdanmurdoch@gmail.com

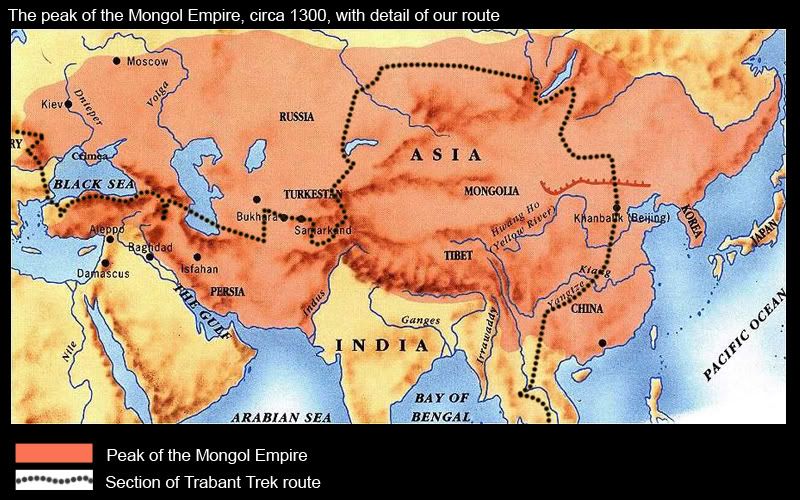

For more of Dan’s blogs visit: danmurdoch.blogspot.com or www.trabanttrek.org