The Gobi, Mongolia

November 19th- 23rd, 2007

By Dan Murdoch

ABOUT a hundred and fifty kilometres south of Ulaanbaatar the paved road ends.

Like a river petering out in the desert it splits into streams, which divide into rivulets, then trickle out into the sands.

There is no single path from Mongolia to China. Instead there are a million tracks beaten into the desert by a million vehicles, a web of trails crisscrossing the plains for 500km. The better-worn paths may be better travelled, but that doesn’t mean they are quicker or more direct. It is a lottery.

We had all sorts of advice about crossing this maze.

Some of the more vague being: “Just head south,”

Some of the more reasonable being: “Follow the train track.”

But the unifying theme of the advice was simple: “Don’t drive at night.”

So I guess when, deep into the night, we lost the railroad and stopped using the compass, we were bound to get lost.

Lost in the desert after sunset there are no discernable landmarks. We may as well have been at sea. Sorry Lynn, forgot the sextant. By 1.30am we had been doing circles for an hour and things were getting a little desperate. It gets seriously cold out there and no one especially wanted to sit in the cars waiting for the sun, which doesn’t rise to 7.30am.

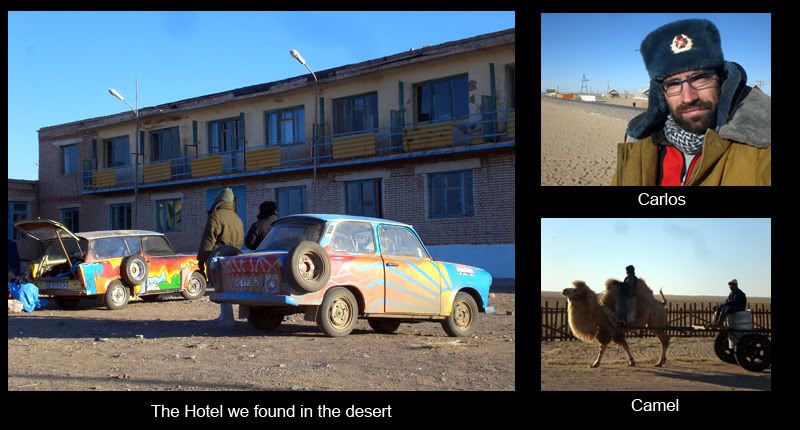

Things have gone wrong throughout this trip, sometimes it seems as if everything is against us. But occasionally the universe conspires to help. From nowhere, deep in the Gobi, a hotel appeared.

Amazing.

There was nothing around it, just this large, crumbling two-storey building alone in the desert. It appeared derelict, but we could see a light on, so I went in with the Johns and stumbled around in the dark, shouting hello and opening rooms. There was a large billiards table in the lobby and gaping holes in the floorboards. The scene was set for a werewolf encounter, or a room full of gun totting desert bandits to appear.

Instead a kindly woman came out and told us we could stay.

Earlier that evening we had dined at a cafÈ that was 150km from Sainshand, our destination. But the woman said we were now 230km from Sainshand. It doesn’t sound too much, but in those conditions we were going no faster than 40kph, so we had needlessly gone a good few hours out of the way when we were in a race to get to China.

We looked on our incredibly inaccurate guidebook map and saw that the train track we were following splits at Airag- one branch goes south south west to the border, the other doubles back on itself and heads north north east into nothingness.

We’d followed that one.

If ever you come this way, stick to the right hand side of the track.

We all shared a freezing room and grabbed a few hours’ kip.

In the sunlight of the next morning I got to look around the hotel: a very strange place, large, but crumbling- who drags a billiard table out here into the desert? I couldn’t help but wonder at its former glory. The woman who had set up beds for us didn’t seem to want any money, but I gave her some anyway.

Round the back I found a small hamlet, five buildings in a square, all of them falling apart and looking unlived in. But the square was full of statues of curly horned goats on plinths- there must have been half a dozen along with a mysterious sitting camel. And at one end was a broken statue of someone in a veil, I couldn’t work out if it was a man or a woman because part of the face had been sheered off. On the top of a dune opposite I saw a pile of heaped rocks.

Maybe this is some kind of religious site? Certainly I see no reason for a tiny hamlet to have so many statues. And why the hotel? Maybe pilgrims used to come here? In the daylight the isolation of the place was even more vivid. We were nowhere.

As we left I saw a signpost with a name on- the only signpost I saw in the desert. It said DANAH TYPYY, which would be Cyrillic (if there was an N in the Cyrillic alphabet) and translate roughly to Danan Turuu. Or if the N were meant to be the Cyrillic backwards N it would say Daian Turuu.

Maybe it has something to do with the Buddhist cult leader Danzan Ravjaa, who was the Fifth Gobi Lord (what a title) in the early 19th Century. Many think he was a living god and tales of his feats abound in these parts. It needs some looking into…

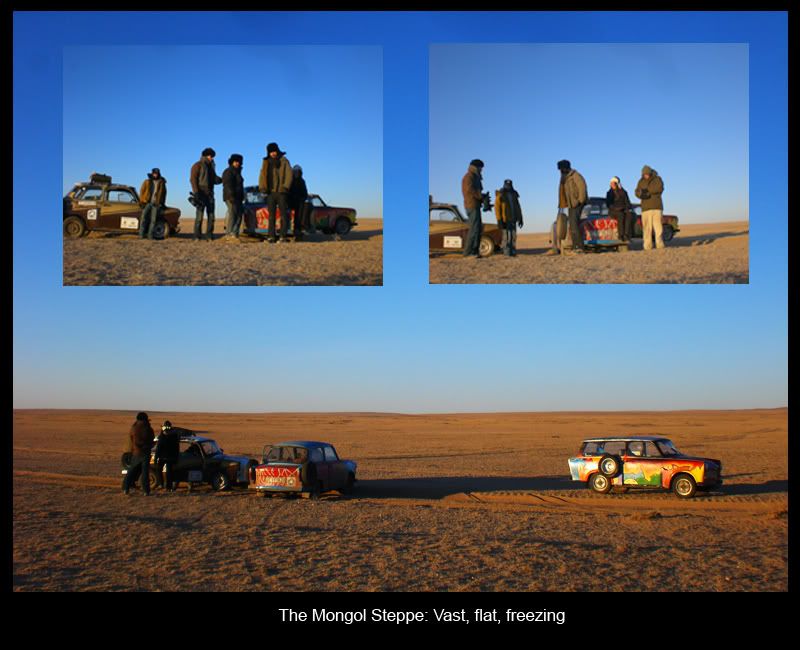

The Gobi (which means desert in Mongolian) isn’t particularly sandy like the Sahara or Karakoum. It is mostly plains, dirty, gritty, flat plains as far as the eye can wander. I don’t think I’ve ever seen such a vast expanse of flatness, except when looking out to sea. Some places it gets grassy, with thick shrubs and a film of yellow. Other places there are patches of treacherous sand, ripe for power slides and wheel spins.

Many of the paths are scored deep into the soil so you have little choice but to follow the heavy grooves. Paved roads are relatively new to Mongolia, but their absence hasn’t stopped people from making their homes far in the wilderness.

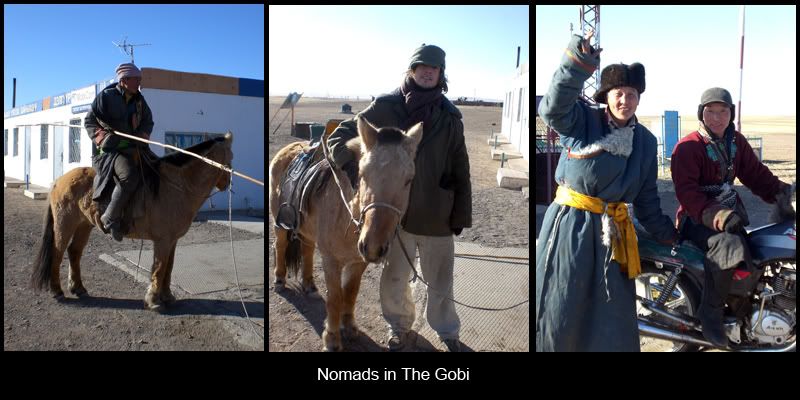

We passed a horseman in traditional robes, held together with a bright sash and wearing tall felt boots over padded trousers, a thick skin hat on his head. The horse wore an ornate saddle of tarnished metal and well-worn straps. The combination looked bright and gaudy among the washed out yellows of the surroundings.

Mongolian horses have always been famous, but not for their size or speed, they are actually quite stumpy animals, looking more like overgrown Shetland ponies than world conquering horses and their hair is thick and long and warm and cuddly. What stands the Mongol horse out from the bunch is its endurance; the beast will keep going until it drops dead from exhaustion.

A few hours after leaving, and when the terrain had began to improve and we were making some decent progress, I had the audacity to tell Carlos that I thought there was a chance we could make it to China today.

Then the leaf spring on Ziggy snapped.

The car was undrivable and, after sending a scouting party ahead, we walked it to a small hamlet by the railroad. The place consisted of five large wooden buildings for living in, painted maroon, yellow and blue, and a bunch of small sheds for livestock. The whole thing was ringed by an unimposing, waste high green metal fence.

The hamlet could have been from Sylvanian Families, or Hobiton. In the middle was a basketball court and a stack off timber. A few of the homes had satellite dishes. It was so neat and pristine it felt like a film set.

OJ: “It’s a home for railway workers. There are about 20 guys who live here. Every day they head out on these little carts and check on their stretch of the railway.”

These modern steppe dwellers live in neat tidy homes rather than tents, and spend their days tending their stretch of the railway, rather than their herds.

The path of progress.

There was a camel tethered to its cart near the hamlet and I went to investigate. I’d never liked camels, having spent three uncomfortable days on a one humped monster in the Sahara a few years back. It spat and bit and sneezed, was ugly and grimy to look at, uncomfortable to ride, and needed to be constantly kept in line.

But this one was entirely different. Beautifully groomed with a long beard that turned into a flowing natural scarf down the length of its long elegant neck, it had a flowering Mohican on top of its head and thick, bushy leg hair above its knees that made it look like it was wearing knickerbockers.

This was one of the famous Gobi camels and I guess I had unfairly lumped the two-humped variety in with their one-humped relatives.

I’ve heard they can go a month without water and then drink 250l in one sitting. That would put OJ to shame.

A few of the locals got the leaf spring out of Ziggy and stared at it for a while before deciding they couldn’t repair it.

We decided to split up. Three of us, Tony, Carlos and I, would drive to Sainshand to try and find parts. Three people in two cars, so that if anything happened on the way we could try and fix it (we had Tony) or dump the car (we had a spare).

It was dark and took about three hours to cover the 85km, and we only lost the train tracks once.

Earlier that day, when we had left Ulaanbaatar, it felt like leaving the arctic. It had snowed quite heavily overnight and the fall had settled deep and undisturbed on the endless flats. It looked like pictures of the North Pole rather than East Asia, but the snow slowly dappled out as it got warmer and by the time we reached Sainshand it was a giddy 4c.

It is a strange little town with some impressive administrative buildings and the whiff of desperation in the air. The focal point is a public square outside the government offices. In the square is an empty public swimming pool, which appeared determined to morph into a sandpit and an unpaved, unloved basketball court with both hoops torn form their backboards. I watched a pack of hounds cautiously sniffing out a new member y a pile of rubbish. At night we watched a woman fighting a man in the street and saw the top of a large new apartment building burning down.

The kids are so cute. They look like little Ewoks with their big woolly hats and backpacks that make their arms stick out funny. They speak like the adults: in strange whisperings. The Mongol language sounds like a gruff gentle fluting, it comes from the back of the throat in rasping, airy grasps. Unlike anything I have heard before, it sounds a bit like the murmurs of extras talking among themselves in a film, all hushed tones muttered under the breath.

The next day we got the leaf spring welded and made it back to rescue the others. In the daylight I could see just how much livestock there is in this part of the desert, where it reaches the lusher plains of eastern Mongolia.

Scores of horses roaming in herds, hundreds of cattle chowing absently, we ploughed through the shrubs, scattering tiny birds. There is life in this harsh environment.

We got the whole team back to Sainshand and stayed the night, then rose early to try and push for China.

The welding on the leaf spring didn’t last long, so Ziggy, and therefore the rest of us, were limited to just 30kph.

Shortly after lunchtime the tracks we were following disappeared into a sand dune. Carlos thought he could cross it and pushed on, but only succeeded in getting Fez stuck in the sand, then tearing up the clutch plate trying to get us out.

The plate was destroyed and we were miles form any life, so we did the repairs out there in the desert.

It was dark by the time we finished so we made a fire out of dried dung and tumbleweed, supplemented by a few posts from the railway fence we were following, and set up camp.

I slept in Fez and probably had the coldest night of my life. Whatever position I tried I got an icy draft, my sleeping bag seemed to radiate cold (this one’s really warm my brother Tobi had told me when he handed it over. It’s not.). I woke up in the night to find a chunk of ice had formed on my hat and where my breath condensed on my scarf it was frozen stiff.

My feet turned to numb aching blocks. I hardly slept, but spent most of the night muttering curses. The others, in the tents, didn’t seem much better off.

The next morning, day four in the desert, we drove long and hard to get to the border before six.

We arrived at five thirty, initially they wouldn’t let us pass, but we begged and made it through Mongolian customs at 6pm. On the China side they had closed up, and for a second I thought we would be stuck between countries again, but we met our guide and he negotiated for us to be allowed across while the cars kept in no-man’s-land overnight.

Finally, nearly four weeks after leaving Bishkek, we were in China.

China.

Ends

mrdanmurdoch@gmail.com

For more of Dan’s blogs visit: danmurdoch.blogspot.com or www.trabanttrek.org

1 comment:

Dan, you are doing a fantastic job of keeping us all updated and look forward to the next one. Please tell Carlos that we have received the postcards and they are all on our fridge. It is good to see that you have made it so far despite all the troubles you have gone through. Greetings from Melody, Hamish and Dave from Budapest. Zoe

Post a Comment