Turkmenistan : A Country You Cannot Leave

Ashgabat to UzbekistanSeptember 1st to 7th, 2007

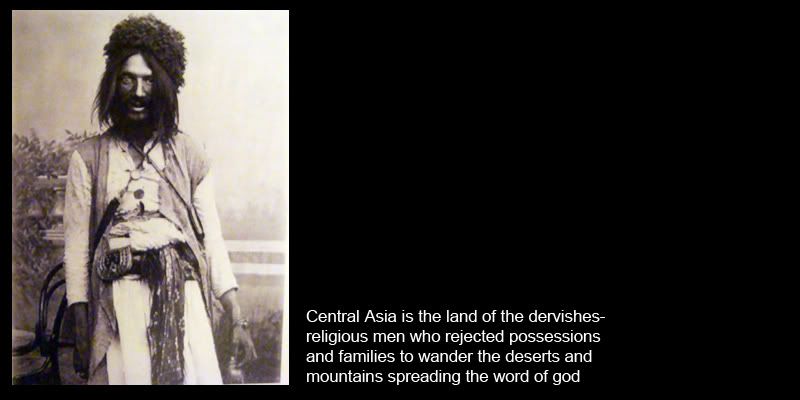

By Dan MurdochNOBODY really knew what to expect from Turkmenistan. Other than the banks of the region’s two great rivers, the Oxus and the Jaxartes, much of the land is untillable, and the tribes of Turkmenistan have long been nomads and herdsman, shifting their flocks across the stretching planes. Central Asia’s heyday was the Silk Road, when incense, dye and cloth passed through from the East, and furs and honey were sent West. But these routes dried up when Europeans discovered a sea route around Africa, and trading power shifted to the Portuguese, Dutch and British.

The region has been sheltered from the world for years, the former sparring ground of great civilisations – Parthians, Macedonians, Huns, Scythians, Mongols, Sajlik Turks and Ottomans had all marched through. But the area had been consumed and hidden by the Russian Bear for a hundred years. The Soviets stifled the region’s exports, mostly slaves and war, until the West had forgotten the centre of its own map.

The country’s government deliberately makes it difficult for tourists to enter, and there is no free press, so it is difficult for outsiders to gauge life in the country.

All we had really heard was a steady stream of rumours and urban myths about the eccentricities of the former President, Niyazov, who died in November:

Once he banned gold fillings. He had them confiscated, melted down and turned into a giant gold statue, which sits in Ashgabat on a rotating platform, so it always faces the sun.

He named the days of the week after his family.

He lived in stunning opulence while his people starve.

He made all school children study his own book.

Once he outlawed beards.

Rumour, conspiracy and half truth.

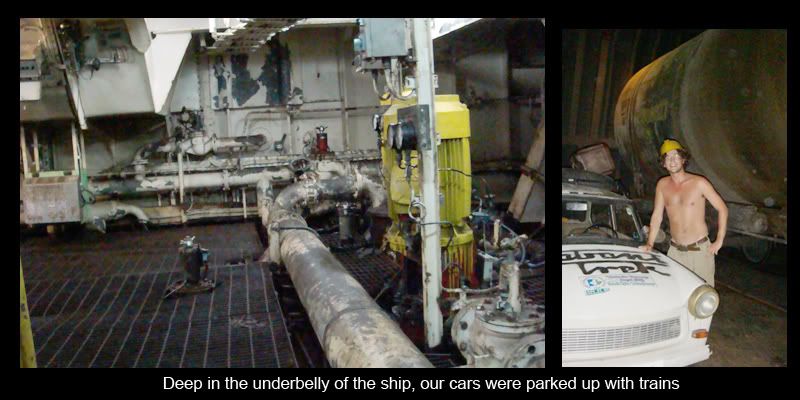

We did know that the terms of our visa meant we would be escorted across the country by a guide, who would meet us at the ferry port. With the guide we’d be up to nine for a while – our maximum capacity. It would be interesting to see how he copes with the rigours of trekking: the breakdowns, the late nights, the wrong turns, the backtracking, the committee meetings…

The guards at the border wore thick safari suits and looked Chinese. Broad Mongol faces, thick black hair, slanted eyes, and chestnut complexion.

But our guide, Ilya, looked like a Belgian professor – mousy blonde hair, milky skin, light blue eyes.

He had been waiting for us at the Ferry port of Turkmenbashi for a week. Good preparation for life on the Trek.

“Do you like camels?” a young looking border guard asked me.

“Um…not really.”

I’d spent three uncomfortable days on the back of one in the Sahara a few years back. They bite, they sneeze, their ungainly gait and ridiculous shape make them a terrible ride.

“They have good milk. You must try it.”

It hadn’t occurred to me to taste their milk.

From Turkmenbashi we drove through the night to reach the capital, Ashgabat, City of Love.

80% of Turkmenistan’s 488,000 square kilometres is desert, and the roads through it are long, straight and sleep inducing.

Swathes of salt lie crystallised in the Karakoum dessert like pockets of snow. The wind has swept the sand into tidy, rippling piles that stretch to the horizon. We drove through a village of one-storey buildings, where cows and camels roamed the streets, and stretched out in the shade or scratched their backs on fencing.

Every hour we would pass another police checkpoint. It was a lottery whether they stopped us or not, but if they did, Ilya would jump out and show our papers.

“Thanks for not asking for money,” Megan shouted at one group as we left, still smarting from the constant ‘taxes’ we had been paying since Azerbaijan.

The Great Silk Road, a sign announced somewhat hopefully, from among the peeling, crumbling low rises and dusty, wooden shops. Women cooked in huge pans over open fires beside the road.

“It reminds me of Vegas,” Megan said as we drove through the Legoland streets of central Ashgabat, “Everything here looks like it was meant to.”

I could see her point, it was all well manicured, perfectly polished, neat and tidy. But nothing in Vegas struck me as pretty and I felt the same sanitised sickness here. It didn’t appear real, not grown organically as the city had developed, but built very deliberately by a man with a strange marble vision.

The giant, marble-slabbed buildings seemed out of place and preposterous. Deliberate ostentation in a country that looked like it had bigger problems to deal with.

Walking through the Ashgabat bazaar, it was easy to forget where I was, there is such variation in the people. Along one aisle you might see a group of tall, high cheekboned blondes with sunglasses and Prada handbags. You turn a corner and see short, squat, leather-skinned old women in shawls and wraps, their wide, flat noses looking entirely Far Eastern.

Others had the large ears of the Turks we’d left in Istanbul, or the big noses of the Armenians in Yerevan.

Big bosomed babushkas aggressively urged thick, clay-oven baked loaves at me.

Looking at the Turkmen faces is like stepping through the country’s history.

Alexander the Great, Ghengis Khan, Timerlane, Catherine the Great – they’re all here.

I asked Ilya why everyone looks so different.

“During Soviet times there were 15 republics and you could travel between any of them, so people from the whole of the union came here. My grandparents came from Russia after the earthquake.”

The Earthquake happened in 1948, a nine or ten on the Richter scale, it flattened Ashgabat in a second, killing 110,000. In typical Soviet fashion, Stalin claimed just 5,000 had died, and sealed off the area for five years so it could be rebuilt.

“After that 70% of people in Ashgabat were Russian. Now it is 2%, most of them went back to Russia in the 90s,” Ilya added.

Turkmenistan was one of the few countries that didn’t want independence when the Soviet Union collapsed. Its economy relied too much on Moscow.

But Moscow shunned the Turkmen, and the country was left in a terrible state. It was in these conditions that Turkmenistan’s communist party chairman, Saparmurat Niyazov cemented his power, wining 98% of the vote at the country’s first elections after independence.

A few years later he took the name Turkmenbashi – Head Of All Turkmen.

His image is everywhere. There are gold statues and busts of him in every town centre. He is painted onto factory buildings and vodka bottles.

The country’s slogan is Halk, Watan Turkmenbashi – people, nation Turkmenbashi.

His book, Rukhnama, Book of the Soul, is compulsory reading, and university applicants must pass an exam on it to gain entry to higher education.

I am reliably informed that the book is mostly nonsense. An attempt to invent a history for Turkmenistan.

That was the biggest challenge facing Turkmenbashi. Trying to create a history, a heritage for his people. To forge a nation, you need a sense of a shared past, some heroes to celebrate, some victories to unite, a sense of commonality. All nations take part in the contemporary creation of their own history – just look at the ceremony and regalia of the British monarchy- entirely invented in the 19th Century.

In that respect Turkmenbashi’s excesses can be excused, he did a good job of uniting the country. Admittedly he invented a history and culture that set himself up as a semi-deity, but most leaders tend to have a bit of ego.

Yes he spent millions on his own architectural projects for Ashgabat while many of his people starved. Yes the buildings are expensive and oversized, designed to flatter Turkmen industry, and Turkmenbashi himself. But it is now an impressive city.

He kept the country away from the Iranian extremism just over the border, and forged trade relations with the West. Turkmenistan was one of the few former Soviet republics to escape the 90s without a complete breakdown in law and order.

The pillar of his foreign policy was to make Turkmenistan neutral – the Switzerland of Asia- and the stability that neutrality has provided has kept the country ripe for foreign investment.

I asked Ilya what he thought: “Niyazov? We loved him. The people here were hungry so they needed a leader. Someone to help them. He did a lot for us. You can enjoy yourself, you can have fun, you can pick up women, but if you have politics, then it’s a problem. Otherwise – no problem.”

So what do you think of Turkmenbashi?

I was breakfasting at our Ashgabat hotel, a bright modern building that we were sharing with a group of 40 cyclists who were riding from Istanbul to Beijing.

The waitress smiled sweetly, “He was a great leader.”

“There are those who say he was a deranged megalomaniac.”

Anger flickered across her face: “He was a great leader.”

She cleared my breakfast and hurried off.

“Careful there mate,” came a South African voice from the next table over. He was leathered, tattooed and drinking vodka. “You don’t want to get anyone into trouble. The whole place is bugged. All the hotel rooms, the restaurants, anywhere foreigners go.”

It could be true. Turkmenbashi was famously suspicious. Even now you are not allowed to film or photograph a lot of buildings.

Turkmenbashi died in November last year, but the new president’s face has replaced his predecessors all over the place, though still Niyazov’s statues stand. It seems the new man is following Turkmenbashi’s lead.

We were told there was a crater in the desert filled with fire. They said it burns constantly, day and night.

So again we headed into the vast barren emptiness – yellow, brown, black and grey sands, bearded with dry brown shrubs that spike your feet. The road began as a main artery, became a vein, then turned into a capillary and fizzled out into the dunes.

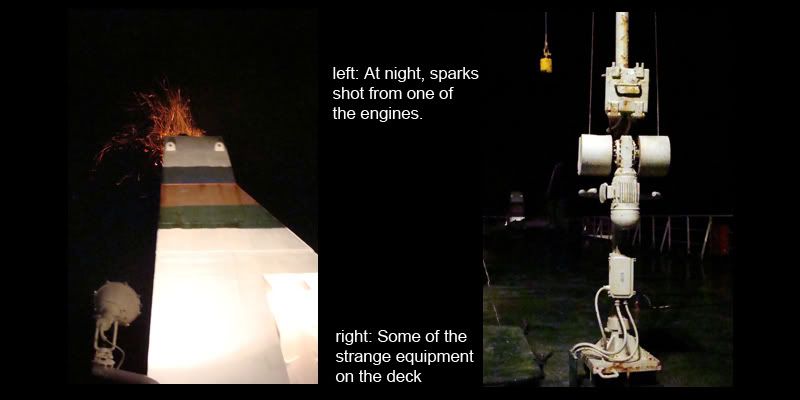

The craters halo was visible from miles around, lighting up the sky like a giant torch. It was far out in the desert, so we dumped the Trabbis and had a construction worker drive us out in an old Soviet truck.

In the waving sands I lost all sense of perspective, and despite seeing the light on the horizon, couldn’t work out how big the crater would be.

But when we arrived there was a collective sigh of relief, then whoops of amazement when the scale of the thing became apparent.

I huge oval hole in the desert, brimming with fire. It must have been 150m across and 50m deep. Shrapnels of sharp rock ribbed up the sides of the pit, gushing yellow and orange flames into the night. Plumes of bright fire shot from jets in the centre of the crater dampening down momentarily, then erupting high into the air. The whole thing glowed like amber, melting in the coals of a campfire.

Dante’s inferno, the fires of hell, Mordor – I half expected Frodo to turn up and hurl the ring in- a truly magnificent sight. I stood at the crater’s edge and felt the bright warmth on my skin, then a gust of wind threw the full force of the heat at me, making me eyelids prickle, and forcing to leap away, shielding my face. It was impossibly hot in there.

I asked the truck driver who had dropped us off where the fire had come from. He did not know, but said it had been there for the 21 years of his life. Maybe forever.

Was this some natural phenomena?

If it had existed for centuries, here in of all places the land of Zoroaster, then surely temples would be all around. Fire worshippers would have had a field day. I could imagine the offerings being thrown into the flaming crater. It would be a wonder with a global reputation.

No, it must be a modern creation. Ilya agreed: “I think maybe there was an explosion here and many people died.” He told me cryptically, digging deep in his vodka sodden mind, but he couldn’t expand or follow the thought any further.

I wondered around the crater looking for signs, and found a bundle of twisted broken metal pipes leading from the ground out into the crater, where they had snapped off and burnt.

It looked like a gas explosions, and it made sense. Perhaps the Soviets or Russians were drilling for gas, when there was an accident, an explosion. The crater caught fire and, rather than explain what had happened, they simply closed off the area and left it to burn out. It smacked of Stalinism.

But the fire didn’t burn out. No one knows how to extinguish the flames, which dive into the ground. It will burn on, until it has sucked all the gas from its reserves deep below the earth’s surface.

The flames threw yellowish light onto a tall dune next to the crater. At the top someone had piled rocks in a sort of monument, the ghostly column flickering like a strobe above us as we laid out mats and slept in the fires warm breeze.

Our guide had met us in a smart shirt, with suit trousers and shiny shoes.

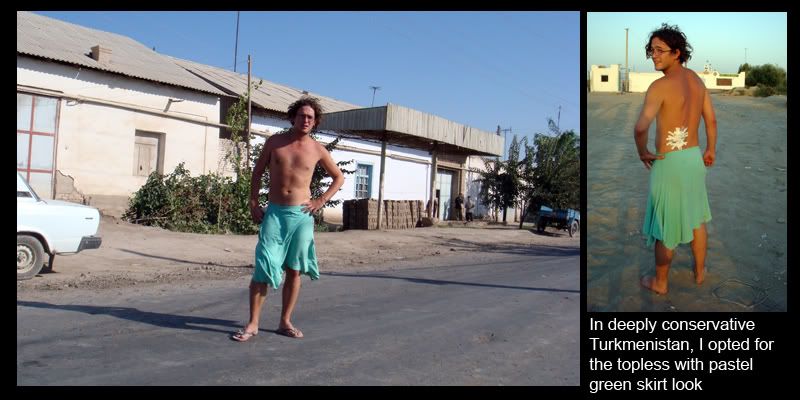

But his dress disintegrated the longer he stayed with us and by day three his shirt was unbuttoned and hanging open, his chest exposed, trousers replaced with cargo pants, his hair scuffed up and his nails dirty.

The Trabant trek affect.

The oil pan on the Mercedes smashed again while we were heading from the fire crater to the border. It was terrible timing. Our visas had just a day left on them, and Turkmenistan is not a good place to overstay your welcome. Thankfully I had struck up a conversation with a man at a nearby bazaar. He gave me a tape of local music, and later happened to pass us sitting on the side of the road.

He invited us back to his for dinner and a place to stay. We ate in the Turkmen style – sharing a few big bowls between everyone, and drank in Russian style, knocking back shot after shot of vodka with fizzy pop chasers.

“I like you Dan, I think you might be Russian,” Ilya told me the next morning.

A curious assessment based, as far as I could tell, on my ability to drink vodka, go to sleep at the table, wear a skirt and fall over in the shower, gashing my back to the extent that I needed medical attention and three injections.

Megan: “Oh god, you’re still bleeding.”

A new word has entered my dictionary. Subcutaneous. As in, it’s a subcutaneous injection- an injection under the skin, but not into the muscle. I had one of those and two intramuscular- they do go into the muscle. I’m not sure what they were, Tetanus maybe, but the next day I developed a fever, cold sweats and diarrhoea.

When a foreigner overstays their visa in Turkmenistan, a committee has to be formed to discuss what to do with them. It takes a day to form the group, a day for them to discuss the issue, and a day to reissue the correct paperwork. God knows what it might have been like back in Soviet times.

Because we had no papers it was dangerous to head into the nearby city, which, like the rest of the country, was swarming with police.

So we were stuck on the Turkmen-Uzbeki border, a strip of dusty soil crowded with queuing trans-nationals and hawkers flogging knock off electronics. Not the best place to recover from a gouge in your back and the shits.

We sat in that sandstorm for three days, while a constant stream of Uzbeks and Turkmen examined the cars, tapped at the chassis, demanded to see the engines and tried to buy things off us. Every day we thought we’d get out of there. But always our guide would turn up to tell us there had been another delay. The incessant attention became wearing and I stopped responding when the thousandth person asked what my name was.

Sorry Turkmen, I’ve had enough.

We had been warned by our guide not to go into the city. We had no papers and our visas had expired, so we could get arrested. But we couldn’t stand being on stage at the border crossing any longer.

Three days of sitting in sand, had got to everyone, so we decided to head into town to find a café to sit, relax, eat and contact our embassies about the problems we were having getting out of the country and the exorbitant fees the travel agency were demanding.

Anyway the traffic cops that line the streets didn’t have cars or radios, just whistles, and we soon learned to speed up and look the other way when we heard a whistle – how could they catch us? It became a cat and mouse game around the city, trying to avoid the cops who’d whistled not waved.

Maybe the game antagonised the cops. We can’t be sure.

Things seemed to be going fine, people were unwinding, relaxing.

Then the police called us out of the restaurant to arrest us because we had dirty cars. The Trabbis had gone 6,000km through dense forests, tall mountains, choking cities and dusty deserts without a wash and they’d picked up a little muck. This is a serious offence in Turkmenistan where automobile care is more important than running water or an ATM.

OJ negotiated, the cops wanted us to go to an expensive carwash. But we decided to get a random local to wash our cars with a bucket for a dollar each.

We had so little money that Ilya paid.

We pulled up in an empty car park overlooked by a block of flats. Within minutes the Turkmen were swarming over us. All ages of them, kids on their way home from school, teenage girls, giggly and practising English, old men wanting to know the cost of the Trabbis, young men wanting to see our mobile phones. Two police cars over looked it all. Things got so crazy a man with a wheelbarrow turned up to sell watermelons.

“Do these people have nothing better to do?” TP asked. Perhaps not. But I guess we’re quite a sight for the locals. J Lov asked what might elicit a similar response in the US. We agreed that if Justin Timberlake showed up at a run down social housing estate, he too would be crowded with locals.

So we’re the Turkmen version of Justin Timberlake.

The attention made the police really riled. The poor chaps had wanted to throw the book at us for having dirty cars, and had ended up policing a mass public demonstration. They got angry and demanded we form a column and follow them. Ilya started to get angry with us and nervous.

There was a lot of discussion and then they led us out off the city and told us never to return. We were banished. They took us to a closed out-of-town bazaar – a Turkmen version of a mall, a couple of acres of empty stands and trucks swarming with mosquitoes. A dusty breeze swept across the place and the police were determined to lock us in.

It caused some consternation: “They want to help you – you cannot stay on the street, it is not safe. They think it is better for you to stay here,” Ilya explained.

Either way it felt like we’d been locked up.

There was a café/bar full of truckers, and it gave me an opportunity to chat to a few people about life in Turkmenistan.

“A few years ago there were people who wanted a revolution,” my source told me, “There were a lot of important people who said a lot of stupid things on TV. But we knew they were not stupid, we knew these people so we believe what they say.

“But about two years ago they all die. They don’t just get killed in one day – it is many things, injections and things over a long time. But they all go.

“I should not be talking to you, it may be dangerous for me. Maybe I disappear,” my source said it with a smile, but he had been drinking vodka, which had lowered his inhibitions or increased his stupidity – either way it loosened his tongue.

“Many people disappear, yes, many people.”

I asked him whether he knew anyone who had disappeared.

“Yes, a friend of a girl I used to work with. He was a political activist who wanted revolution. One day he was just disappeared. Also the Turkmen ambassador to China. The government said he sold fighter planes and stole the money, but nobody believes this.

“Yes many people disappear. But this is the way it is. It is like this since Stalin, it has always been the way.

“I hope I am still alive in the morning.

“People have many thoughts of revolution. But with so many police everywhere, always watching, there is no chance of revolution. People think of it but there is no way.”

Carlos and I stayed in the café for a few hours to learn Russian swear words from farmers. When I wobbled out of the place after one to many toasts I found Ilya walking through the darkness.

“Two men from the KGB are here.”

Words to send a chill down anyone’s spine.

Why?

“It’s complicated, things are very strange. It is a long story. Over there are many drug makers,” he gestured towards the far wall of the compound, “So they are here to protect you.”

I said that I wanted to meet them, so he took me over. The officers were typical Turkmen opposites. A tall, dark haired man in his 30s with an intelligent face who reminded me of the detective in Georgia

His assistant was squat and plump with a broad hazelnut face, wearing what looked like a GAP outfit – fitted stripy jumper, dark jeans and loafers. They seemed friendly enough. But it was a strange feeling being watched. I couldn’t get used to it.

I asked Ilya whether they were here every night: “No, they are only here now to look after you. If anything strange happens you must find them.”

I wondered what he meant by anything strange, but he waved me away and talked with them in Russian.

We wandered back up to the café and Ilya opened up a little: The KGB is now known as the KMB – the Committee of National Defence. Different name, same job.

Are they here to protect us or watch us? “Yes they protect you, but it is also desirable for them to watch you.”

Are we in trouble?

“Not you. But maybe me. This could be a problem for me. Maybe I disappear.”

He told me that in Turkmenistan there are three police for every person. “At night in Ashgabad there are 5,000 police on the street. The population is just 600,000 people, but they must watch them. These police, they don’t wear uniform. They are undercover, just watching. I know because I used to have a job delivering to an underground station. I saw many police there.

“Until a few months ago this whole province was closed off. You needed a special permit to go here, it took two weeks to get one even for me. It is because it is on the border with Uzbekistan. But the new president he makes it free to go anywhere.”

I asked one of the KGB why the area was closed off, when Turkmenistan had good relations with Uzbekistan and had declared neutrality: “It is the border,” he explained, “You must be careful.”

“Yeah, we keep a pretty close eye on the Welsh I told him,” and he laughed.

Half an hour later I heard shouting from by the gate to the compound. I faked taking a pee and went to investigate – saw Ilya getting dragged away by some official. He returned ten minutes later with a thick set Turkmen.

“We have to move,” he told me, “You are honoured guests. It is not right for you to stay here in this bazaar.”

I couldn’t help but laugh – honoured guests who’d been banished from the city and imprisoned in this mossie infested sandpit with the KGB for company.

“These people are from immigration, they say it is not right that foreigners are camped here, just five kilometres from the border.”

We had spent the previous three nights camping literally on the Uzbeki border.

“You must stay in a hotel.”

It was ridiculous. The street cops had put us here, the KGB had decided just to watch us, and now the border police wanted to haul us back into the city.

“It is illegal for foreigners to stay outside. They must be registered at a hotel. This is the law.”

We had no choice.

I haggled over price and managed to get them down to $4 per person for the hotel– down from the $17 we had been quoted that afternoon.

We drove back in convoy with police, immigration and KGB to the worst hotel I’ve stayed in. We crammed in, four to a room, and I spent the whole night knocking mosquitoes and bed bugs off me, and trying to avoid the gash in my back. I rose early just to get out of the filthy pit and again waited for the Turkmen to let me leave their country.

But more delays, more paperwork, more problems with our guide. We finally got our visas stamped, but the border closed, so we spent yet another night camping on a sandy crossroads.

“I'm sick of this shit. I promise you now I am never coming back to this country,” was OJ’s analysis. The country had divided opinions. Certainly OJ, Lovey and Tony had hated the place – constantly letting their exasperation show. But I felt a little more reserved. We were the ones who overstayed our visa. Although it wasn’t our fault that the Mercedes broke, we had to deal with the consequences – four days of bureaucracy. We knew when we entered the country that we weren’t meant to go anywhere without a guide and all out papers, that we should be registered at a hotel in every city. We were told that not cleaning our cars would attract unwanted attention. But we just ploughed on, convinced of our inalienable right to freedoms, which over here have yet to be won. Turkmenistan operated a different system, and I was pleased to get an understanding of it, if only to more greatly respect the liberties I take for granted back home.

I got up full of hope that we’d make it across, five days later than we’d planned. But within minutes of breaking camp and pulling away, the gearbox broke on Fez.

It was embarrassing being towed up to the border.

“People have crossed borders by foot, on planes, by boat and on trains. But how many people can say they’ve been dragged across a border?”

Thanks TP.

We got there at lunchtime, so of course the border was closed. We were all hot, thirsty and frustrated so Tony and Zsofi decided to head up the road in Dante to find water. An hour passed, they opened the border, we began the process and another hour passed.

We started to get concerned, but by now everyone was so numb to the delays we just sat and waited.

We were in a totalitarian, isolationist, pariah state, hidden away in central Asia, impervious to all Western influences but one. The all-pervading power of euro-cheese.

Even here, on the Turkmen-Uzbek border, they play Steps.

Finally our guide heard rumours through the grapevine that they had both been arrested in town for not having any papers.

Plenty of groaning, but Ilya went to negotiate and we finally got them back shortly before 5pm and managed to cross the border into Uzbekistan.

It was like escaping a concentration camp – Carlos and I whooped and high fived when we saw the ‘Welcome to Uzbekistan’ sign. Through some strange quirk of fate I entered the country shoeless and topless behind the rest of the cars. I genuinely felt like I was in a prisoner exchange, crossing the 500m of no man’s land between the countries.

The guards kindly stayed open late to process us, an then let us out into the Uzbek night. We were still towing Fez.

Ends

Mrdanmurdoch@gmail.com