Khiva, Uzbekistan

September 7th and 8th, 2007

By Dan Murdoch

WHENEVER we enter a city, it is Trabant Trek custom to drive around it in laps, hopelessly lost, becoming more and more stressed as people’s various wants fail to be sated. Some of us need internet, others food, for some the priority is a bed, others need a bar. This new city dance does serve to help orientate us, but also tends to ensure we arrive in frustrated mood, having spent an hour pissing about.

Having already passed one Khivan junior school three times to the sound of loud cheers, we should have known that parking outside would attract a lot of attention. We were swamped with kids in uniform. Initially they circled us guardedly, but soon the braver souls piped up with Asia’s favourite question: “Where you from?”

This question must be ingrained in the locals from an early age – either that or it is the only English that older folk remember from school.

Whichever way, for many of us, it has become the single most infuriating question of all time.

I may be sitting, working, reading, talking, even sleeping, and someone will approach, tap me on the shoulder and insist: “Where you from?”

“England.”

“Oh.”

Then just stares. No follow up. For me the silence used to be vaguely awkward, although the locals always seem happy enough to stare. But now I enjoy the silence, imagining they might feel some discomfort. I hope that every second that ticks by they are realising the futility of their question. What were they hoping to get from that single use of dodgy English? Did they really need to wake me up? What did they think would come of this new information?

Even as I write this, sitting in an Uzbek café, I can hear one man asking a boy next to me where I am from.

Now I realise why all those beer-bellied, builders get a British Bulldog tattooed on their arm. It is so, when they are on holiday in the Costa del Sol, drinking Stella with their shirt off, the answer to the question on everyone’s lips is emblazoned garishly across their upper arm.

I am considering my first tattoo: Britannia, riding a bulldog, draped in a Union Jack, underlined with the words “English, so sod off.”

I was served an eclectic breakfast at my hotel- honeyed figs, sweet oat biscuits, a fried egg, strips of tomato wrapped in baked eggplant, cheese sausage an sweet, watery tea- before I wondered off alone into Khiva.

Khiva is a strange place. There has been a city here for millennia, but its hey day was the silk route and the slave trade. When, in turn, they dried up, the city fell into disrepair - a Russian protectorate, slowly dieing in the desert.

But the Soviets decided to make the best of the place embarked on a huge programme to renovate Khiva in its original style. This meant forcing out many of the inhabitant of the old, walled city and sending them to live in new Soviet concrete apartments, and rebuilding their former homes.

The result is a sort of living, outdoor museum.

Everywhere the sound and remains of workmen scrubbing the place up, replastering, tiling, hammering.

People do live here, but it feels like a mock up. The town doesn’t feel lived in. Where is the detritus of thousands of years of existence? Signs of the past lost in the newly wattled walls. I passed a chunk of carved stone, rising from the middle of a narrow street. All that remained of a grand pillar – what mighty arch did that pillar once support?

And why such empty streets? Khiva felt like a ghost town, and I wanted to see the vibration of its ancient past, but instead felt the sun dazzling off the newly buffed city walls.

There are a few signs of life. Baked clay ovens stand outside some homes, they look like giant termites nests, with gaping sooty holes in the top. Only riveted cart tracks in the ancient stone paving betray thousands of years of existence.

As a prototype for future restoration projects, I'm not convinced. Would Stone Henge bear the same ethereal magic if it was scrubbed up and polished, its fallen stones righted, its alter restored. I doubt it. Part of the beauty of visiting such monuments is seeing what hand time has dealt them.. Their decrepitude tells its own story.

I wonder how the people of Khiva feel about the ‘restoration’ of their city. Many of them were moved out of the old city walls and into the new Soviet style neighbourhood, that now hovers in Khiva’s orbit.

Some remain, still collecting water from the well, and cooking in the their shady courtyards.

But gone is the horror and the majesty. Hundreds of thousands of slaves passed through here, a place where men were thrown into sacks with ferocious animals, were slaves were nailed to the city gates by their ears. The Hungarian traveller Arminius Vambery famously arrived in 1863 to see eight tribal chiefs laying on their backs in the city’s main square. The Khan’s executioner was gouging out each of their eyes in succession then wiping his knife on their beard. Any cruelty you care to imagine was wrought upon Khiva’s inhabitants and the nomads of the surrounding desert. As late as the 20th Century the cities progressive vizier was beheaded.

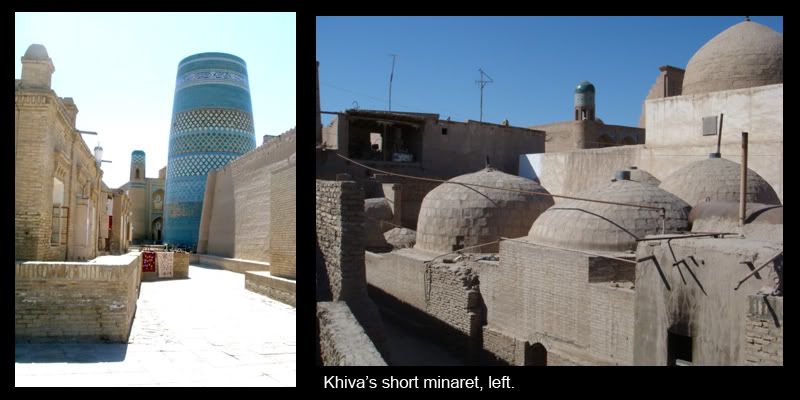

I passed the Kalta Minaret, the ‘short minaret’, a giant, chubby oil drum, dazzlingly adorned with bright turquoise and blue tiles, it’s scale dominates the skyline and stands as the city’s central monument to the Khan’s ambition, stupidity and unflinching ruthlessness.

Commissioned in 1852 to be the tallest minaret in Central Asia, the building’s architect was called to a secret meeting in Bukhara, Khiva’s great rival. The emir of Bukhara asked the architect to build him an even bigger minaret after he had finished in Khiva. When word of this meeting reached Khiva, the Khan ordered that the architect be thrown from the top of his own minaret. Unfortunately the minaret was nowhere near finished and stood just 30m tall. The fall only crippled the poor architect, so the Khan ordered that he be dragged back up to the top and thrown off again, repeatedly, until he died.

No-one finished the thing after that, and no-one is sure why. Can’t imagine…

I stumbled upon the Khan’s yurt – the large round tent he would have slept in during the winter. It sat on a dais in a palace courtyard beautifully tiled in luminous blues and supported by great wood carved pillars. I couldn’t help but wonder how many people had met their end in that cool, bright chamber.

Just like cities in the west, Khiva has its own financial district. Not quite a Wall Street or Canary Wharf, actually it’s a bunch of men sitting around the bazaar, looking bored and fanning themselves with huge stacks of cash.

Currency is an issue in Uzbekistan. With the highest denomination of bill being worth about 40p, you have little choice but to wheel around buckets of the stuff, and when I asked to change a $50 bill a local had to run out back and chop down a small forest to make the notes.

Strolling among the stands of walnuts, raisins, almonds, mink hats, wolf skin waistcoats and surprisingly large amounts of toiletries, it wasn’t difficult to imagine the place filled with the slaves that made the city rich.

You enter the bazaar through the East Gate, or Executioners Gate, a long dark passage with grated alcoves on each side where the slaves would sit and starve until they were bought. Looking into the dark cells, you can still sense the despair that the Persian, Turcoman and Russian slaves must have felt. A Russian slave would cost you four good camels. A Persian just a donkey.

The rare visitors that made it to Khiva and back alive described seeing thousands of slaves manacled together in the market. Those who tried to escape would be nailed to the city’s east gate by their ears and left to bake in the extreme Uzbek sun.

Ends

mrdanmurdoch@gmail.com

No comments:

Post a Comment