Samarkand, Uzbekistan

September 13, 2007

By Dan Murdoch

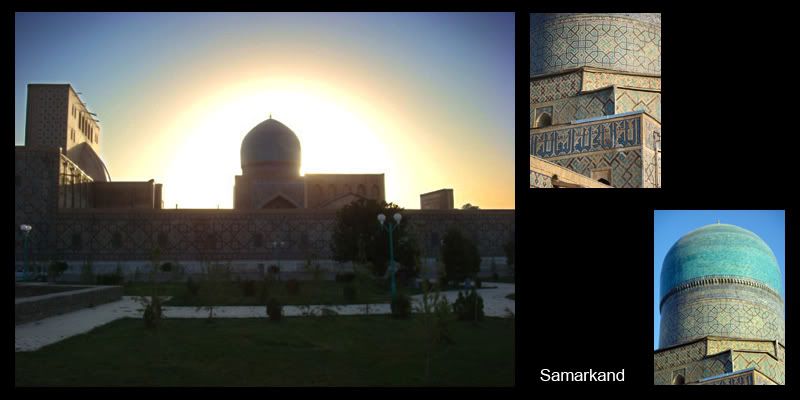

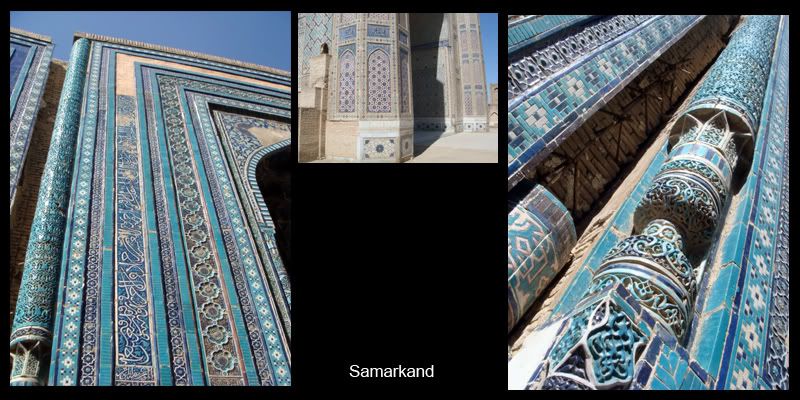

LONDON is big on stone, but here the thing it tiles – clay baked, aquatic colours, pieced together in delicate mosaics that shimmer across and inside buildings.

If ever you need someone to retile your bathroom, I would recommend an Uzbek.

People have lived and traded here since before Christ, even Alexander the Great was struck with wonder at the city. But Ghengis Khan sacked and levelled the place, leaving it a shell until another famous Mongol leader made it his capital.

Fourteenth Century Samarkand was the centre of an empire so remote that Europe new it mostly from the raids coming across its borders. The hordes sacked and pillaged their way across the Caucasus, Middle East, India and deep into Eastern Europe, destroying what they couldn’t steal.

The man who created the empire was Timur the Lame, Timurlane. A petty chief from a small Mongol settlement 50km from Samarkand. His reputation is hero and villain, neatly encapsulating the paradoxes that history knows of him.

He marked the cities he sacked with huge pyramids of human skulls, 80,000 counted in a heap in Baghdad. A keen chess player, he invented his own, more complex version of the game, with twice as many pieces and a larger board. Historians count the numbers he slaughtered in the tens of millions. A lover and collector of fine art, the illiterate Khan installed galleries of neat Islamic inscriptions in his palaces, but could never read them.

His empire stretched from Poland to Delhi, and although he sacked much of what he conquered, he took artists, scholars, philosophers and craftsmen back to Samarkand, which became a glorious hub of creativity, masking Timur’s own dispassionate mercilessness.

And despite his terrifying reputation, the travellers and traders who returned from the empire’s hub spoke of a vast and beautiful city, that became romanticised in Western imaginations. To Poe, Marlowe and Keats this was a city that encapsulated the majesty and mystery of the east.

But the empire crumbled, and so, as the Silk Road withered, did the city’s influence. Though Timur’s legend lives on.

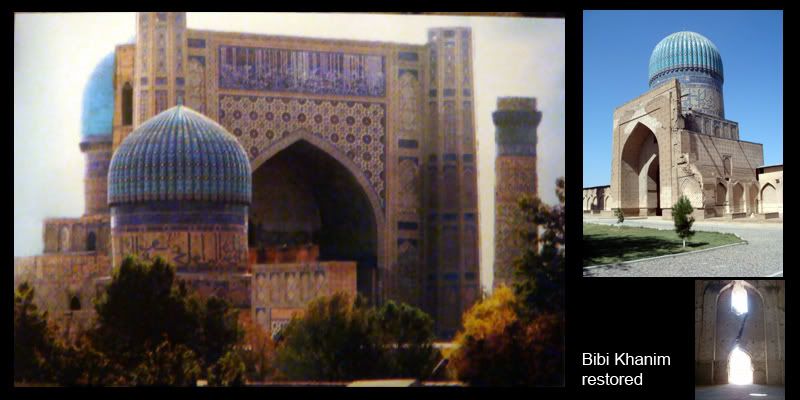

Even now the city’s skyline is dominated by the imposing turquoise dome of the Bibi Khanim Mosque, built using the riches looted from India in the winter of 1398 when Timur sacked Delhi and beheaded 100,000 prisoners. Ninety elephants were needed to bring the haul back to Samarkand.

The mosque’s dome towers over the modern buildings that surround it, as if it were built by a breed of giants or aliens. Arriving at its gargantuan arch it is easy to imagine how dumbstruck a foreign traveller would have been in the 14th Century. There would have been few other monuments of such height and scale in the known world.

But the buildings ambition was also its undoing. The great dome of the mosque was too big, within years of completion great cracks had appeared in it and the buildings quickly became unsafe. This is earthquake territory and perhaps the shifting sands undid the construction. But the dome is a nice analogy for the end of all great empires – they reach their zenith, and the fulfillment of their own opulent glory is also their death sentence. Timurlane’s empire, like his architecture, became too big, too overstretched and ultimately crumbled from within.

Carlos told me a legend of the mosque. It was commissioned by Timurlane’s wife while he was away fighting. She wanted it to be a surprise for him upon his return, but the architect responsible became infatuated with the queen, and on the point of completion demanded a kiss before he would not finish the job.

“Because the queen was a slut she kissed him,” Carlos explained, “They probably did more than that, but the book did not say.

“So when Timurlane got back, he hears about this and he is not happy. The architect of course gets killed, he’s a stupid. But then Timerlane orders all women wear the veil across their face so that no man can see their lips and then they wont be filled with the desire to kiss them.”

Interesting. But probably rubbish.

The best story is every guidebook’s favourite.

An inscription on Timurlane’s mausoleum warned tht anyone who disturbed the great king’s tomb would unleash war on the land. In 1941, Soviet archaeologists opened up the cracked jade tomb that had sat in the Samarkand necropolis for five hundred years. Inside they found the perfectly preserved body of a short man, with mongol features, who was lame on his right side. Flecks of muscle still clung to his body, and a Mongol moustache still whisped across his lips.

Within a few days Hitler launched Operation Barbarossa, the invasion of Russia.

True story.

After Timur’s death a succession of leaders followed, but his grandson Ulugh Beg is best remembered for his progressive vision and love of the sciences. Begh built a huge observatory that calculated the exact length of a year to within a few seconds of modern computers.

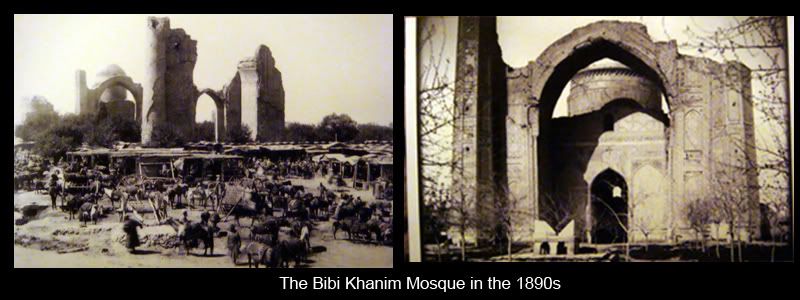

It is a credit to the Soviets that the buildings here have been so meticulously restored. By the end of the 19th Century they were little more than crumbling ruins. Many of the domes had collapsed, minarets fallen in on themselves, tiles and mosaics littered away. And that was before the great earthquakes that struck in the 1890s. They left Samarkand a hollow shell of its former glory.

But the Soviets went about the renovation with vigour. Their work is magnificent. Once again the buildings gleem with the reflection of millions of mosaic tiles.

The necropolis here has some of the best examples of tile work. They have stood here for millennia, even Genghis Khan’s troops refused to touch them. The mausoleums stretch back to before Timur’s time. Shirin-Beka-Oko was built by Timur for his sister in 1385. Inside it is beautiful cool blues and crisp whites. But the renovators have painted on the designs, which I imagine would have been tiled originally. The effect is crisp, clear and impressive, but somehow false.

Opposite the entrance, stands the Shadi-Mulk Oko, built for Timur’s niece. The tiles here are actual originals –the chipped and faded mosaics don’t shine as crisply or brightly, but they look and smell original. You can see that 14th Century ovens baked the tiles, 14th century hands painted the individual pieces and then pieced them together like a huge jigsaw.

The restoration of Samarkand is so stunning it has forced me to reassess my thoughts on Khiva. If Khiva had looked as ruined as pre-restoration Samarkand would I have gone there at all?

The city’s centrepiece is the Registan, a town square, surrounded on three sides by grand buildings. I can imagine Timur returning to the Registan with trophies from his latest conquest, the sides flanked by the glorious symmetry of the madrassas, which loom ineffable, reflecting the immutability of god.

Now the place has a swimming pool atmosphere. All those watery tiles and the strict tourist police blowing on whistles to keep visitors in line, sounding like lifeguards warning children not to dive in.

I wish I had stayed longer. But as ever we are at the whim of immigration officials, who have seemed determined not to issue us with decent length visas.

So we left for the short trip to the Tajik border, where we were met by a refreshing lack of paperwork and security.

Ends

mrdanmurdoch@gmail.com

No comments:

Post a Comment